Ben Thompson is the founder of the subscription newsletter Stratechery. He previously worked at Apple, Microsoft, and Automattic, where he focused on strategy, developer relations, and marketing. I love the way he thinks and writes. I always look at something in a new way after I read his writing. Thompson has said about the nature of his work: “I don’t think there are enough writers talking about how things work from an economics or business perspective. I try to ask ‘Why do businesses do what they do?’”

- “Zero distribution costs. Zero marginal costs. Zero transactions. This is what the Internet enables, and it is completely transforming not just technology companies but companies in every single industry.” “Aggregation Theory is a completely new way to understand business in the Internet age.”

Aggregators create platforms, which are a type of “multi-sided market,” which I have written about before on this blog. Multi-sided markets bring together two or more interdependent groups who need each other in some way. Uber, Lyft, eBay, and Airbnb are examples of a multi-sided market, which are sometimes called platforms. Each of the four businesses I just mentioned is also an aggregator. Every aggregator operates a platform, but not all platforms are aggregators.

An aggregator has three essential characteristics:

- Products sold by an aggregator are digital and therefore have zero marginal cost;

- These digital products have zero distribution costs since they are delivered by the internet; and

- Transactions happen via automatic account management, credit card or other electronic payment system.

Google and Facebook are examples of how aggregators can create a rapidly scalable and profitable business at previously unimaginable scale and speed. Ben calls these two companies super aggregators:

“super-aggregators [have] zero transaction costs not just in terms of user acquisition, but also supply acquisition, and most importantly, revenue acquisition, and Google and Facebook are the ultimate examples. The vast majority of advertisers on both networks never deal with a human (and if they do, it’s in customer support functionality, not sales and account management): they simply use the self-serve ad products.”

Another way of thinking about this aggregator phenomenon is: an aggregator is a platform on steroids and a super aggregator has twice the steroid dosage. The world has never seen anything like aggetators before because the world can never been so digitally connected.

One aspect of aggregators that people can tend not to see is: because being an aggregator is based on network effects, their competitive advantage is strong but brittle. The idea that an aggregator cannot be displaced bu a disruptive competitor does not map to historical record of the technology industry. There is an elephant’s graveyard in the technology industry that is not only large already but destined to grow. For example, a June 2016 academic paper points to these companies as cautionary tales for any technology that thinks its future is assured:

Burroughs, Sperry Univac, Honeywell, Control Data, MSA, McCormack & Dodge, Cullinet, Cincom, ADR, CA, DEC, Data General, Wang, Prime, Tandem, Daisy, Calma, Valid, Apollo, Silicon Graphics, Sun, Atari, Osborne, Commodore, Casio, Palm, Sega, WordPerfect, Lotus, Ashton, Tate, Borland, Informix, Ingres, Sybase, BEA, Seibel, PowerSoft, Nortel, Lucent, 3Com, Banyan, Novell, Pacific Bell, Qwest, America West, Nynex, Bell South, Netscape, Myspace, Inktomi, Ask Jeeves, AOL, Blackberry, Motorola, Nokia, Sony.

Thompson believes that aggregation theory has “disrupted disruption.” In making this argument Thompson describes unique attributes of some aggregators:

“instead of some companies serving the high end of a market with a superior experience while others serve the low-end with a “good-enough” offering, one company can serve everyone…. it makes sense to start at the high-end with customers who have a greater willingness-to-pay, and from there scale downwards, decreasing your price along with the decrease in your per-customer cost base (because of scale) as you go (and again, without accruing material marginal costs). Many of the most important new companies, including Google, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Snapchat, Uber, Airbnb and more are winning not by giving good-enough solutions to over-served low-end customers, but rather by delivering a superior experience that begins at the top of a market and works its way down…”

Being an aggregator is fantastic if you can make it happen, but it is non-trivially hard to do so. Hundreds of big and small firms fail trying to become aggregators in different categories every year. Very few aggregators ever achieve significant scale. The payoff for becoming a successful aggregator is so massive that many people are willing to invest in attempts to do so. Thompson makes clear that it is possible to have a wonderful business result and not be an aggregator. In fact, almost all businesses are not aggregators.

In the case of an aggregator, Thompson writes that: “the network should be generating an improvement in benefits that exceeds the cost of acquiring customers, fueling a virtuous cycle.” He is describing the scalability of the business which I have also written about on this blog (you can find a link to this post in the Notes below).

The high scalability of the business of an aggregator is a wonderful business attribute to have, but it is neither essential or common. Thompson adds that for a business that is not a aggretator: “The keys are positive unit economics from the get-go, and careful attention to profitability. The reason this matters is that these sorts of companies are by far the more likely to be built.”

The high scalability of the business of an aggregator is a wonderful business attribute to have, but it is neither essential or common. Thompson adds that for a business that is not a aggretator: “The keys are positive unit economics from the get-go, and careful attention to profitability. The reason this matters is that these sorts of companies are by far the more likely to be built.”

There are real world total addressable market top down constraints that would prevent too many Google or Facebook sized aggregators being created in a given decade. Fred Wilson has written about this topic in a clear way several times: ” If $100bn per year in exits is a steady state number, then we need to work back from that and determine how much the asset class can manage.” You can take that $100 billion number up a bit but not too far. As an example, in the US venture exits have looked like this:

- “Apple and Amazon do have businesses that qualify as aggregators, at least to a degree: for Apple, it is the App Store (as well as the Google Play Store). Apple owns the user relationship, incurs zero marginal costs in serving that user, and has a network of App Developers continually improving supply in response to demand. Amazon, meanwhile, has Amazon Merchant Services, which is a two-sided network where Amazon owns the end user and passes all marginal costs to merchants (i.e. suppliers).”

Thompson is pointing out that it is possible to be an aggregator and at the same time own and operate other platforms which do not rely on aggregation. In fact, the creation of the aggregation-based business can be enabled by the existence of the platforms that do have products with marginal costs and that are not fully digital. The economies of scale that exist for these other non-aggregated platforms can create significant barriers to entry. The Apple and Amazon examples described by Thompson are cases which illustrate the point about physical economies of scale sometimes reinforcing demand-side economies of scale (network effects). The best opportunity to connect an aggregated digital platform with one that is physical is if they are complementary products like mobile phones and apps.

- “Words by themselves are easily copied. They’re not necessarily worth anything in and of themselves.”

What Thompson describes in the two sentences just above is a key enabler of the aggregation phenomenon. To illustrate with an example, the words in bold were “cut” from an interview of Ben Thompson and inserted in this blog post. This is possible because of a legal doctrine called “fair use.” Small snips of copyrighted material may, under certain circumstances, be quoted verbatim for certain purposes because of this doctrine.

When I made a digital copy of those sentences no one else was denied access to those words (words are non-rival). In contrast, if I had instead stolen Ben’s phone, he would no longer have a phone (a phone is rival) and he would be pissed at me. Ben’s words can be made “excludable” if he moves them behind an effective paywall which he does with parts of Stratechery. This is tricky to do because the ideas that the words convey are not excludable. Non-rival goods have very different economic characteristics than goods like an automobile which are rival.

The great news for Thompson’s business model at Stratechery is that his actual words are super valuable even though his ideas have spread far and wide. Almost every newspaper has reached the conclusion that paid subscriptions are the business model that can best assure their future. In contrast, traditional advertising-supported journalism does not face an attractive future. This is a big societal problem since journalism is a valuable public good like education, national defense, lighthouses or mosquito control and in the past it was advertising that supported that model for the mass market. Societies need an educated electorate, but it is unclear how that will happen in the mass market given the collapse of the advertising supported business model for journalism. The mass market appears unwilling to pay for news via paid subscriptions, even though more affluent people are willing to do so. How will mass market customers get their news in this new era for journalism business models?

The monetary cost of me creating this blog post was approximately zero. My revenue is also zero since I have no paywall or business model. My purpose is educational and to get more people reading Thompson’s work. I like him and want his business model to succeed since we need to find new ways to fund people who are creators like him.

- “Because aggregators deal with digital goods, there is an abundance of supply; that means users reap value through discovery and curation, and most aggregators get started by delivering superior discovery.” “The power has shifted from the supply side to the demand side.” “Value has shifted away from companies that control the distribution of scarce resources to those that control demand for abundant ones.” “The goods ‘sold’ by an aggregator are digital and thus have zero marginal costs (they may, of course, have significant fixed costs).”

In a recent blog post I discussed how hard is was for Alton Brown to get distribution for his television show Good Eats when there was only a few cable channels which might be interested in his work. Now that streaming platforms like YouTube have arrived, distribution is not the most critical problem. The challenge now for a creator of content is discovery. For example, software from a provider like Unity makes it far easier than it was in the past to create a video game, but it is hard to get customers to discover it. An aggregator like Valve has been able to capitalize on that phenomenon. If you are not a gamer, you may not know about Valve. It is a private company based in the Seattle area and is the creator of Steam, a game platform that distributes and manages thousands of games directly to a community of more than 65 million players. Steam Spy estimates that over 5,000 new games launched on Steam in 2016 and that the revenue generated by paid games on that platform was $3.5 billion that year. Valve reportedly has only a couple of hundred employees so revenue per employee is astronomical. This illustration from Stratechery shows how Airbnb has become an aggregator and a similar illustration could be created for Valve’s Steam service.

- “The linchpin on which everything else rests: aggregators have a direct relationship with users.”

The markets in which a successful aggregator has been created are different from single-sided markets like a grocery store in that the platform enables direct interaction between the “sides” of the multi-sided market and the aggregator extracts a fee for enabling that commerce. Importantly, there are no distributors between the aggregator and the sides. This is critical since the data that customers provide about their needs and desires is the source of competitive advantage in the aggregator’s business. For example, Uber and Lyft know a lot about riders and drivers which they use to create the service and add value. But the sides of these electronic marketplaces do interact directly despite their direct relationship with the aggregator. For example, the Uber or Lyft drivers transport the riders. Similarly, Airbnb relies on owners to provide the facilities that people pay to use as accommodation. The owner providing the place to stay and the occupant paying to use the facility deal directly with each other on the platform but Airbnb still earns a fee on the transaction.

- “The fundamental nature of the Internet makes monetizing infinitely reproducible intellectual property akin to selling ice to an Eskimo: it can be done, but it better be some really darn incredible ice, and even then the market is limited.”

I have been arguing on this blog and elsewhere that the nature of business has been fundamentally changed by phenomena like the internet, mobile networks and data science. One thing that is different about the nature of business today is what is sometimes called “SKUmageddon.” There are so many new products in markets that it can be hard or impossible to get discovered. When I am moving through the aisles of a large supermarket today I can’t help but think about how many products there are. To get sold those products in the grocery store must be darn incredible. As another example, SteamSpy estimates that there are this many video games on the Steam platform:

- “Once an aggregator has gained some number of end users, suppliers will come onto the aggregator’s platform on the aggregator’s terms, effectively commoditizing and modularizing themselves. Those additional suppliers then make the aggregator more attractive to more users, which in turn draws more suppliers, in a virtuous cycle. This means that for aggregators, customer acquisition costs decrease over time; marginal customers are attracted to the platform by virtue of the increasing number of suppliers.”

Digital systems inherently enhance the power of positive and negative feedback loops by removing friction. The feedback loops can lead to a phenomenon called “cumulative advantage,” which is a situation where something gets more successful the more successful it gets. Some people forget that “cumulative disadvantage” is also just as powerful, which is a situation where something gets less successful the less successful it gets. Businesses like Blackberry or MySpace can fall as rapidly as they rose. Nassim Taleb points out that we live now in Extremistan where: “there’s Domingo and a thousand opera singers working in Starbucks.”

- “Getting started takes nothing more than an email address. There is no server software to install, no contracts to sign, and you don’t even need a credit card.” “The truth is that because so many folks can now get started it is that much harder–and more expensive–to cut through the noise.”

It has never been easier or cheaper to start a business. This is good news and bad news. The good news is that it is easy to start a business. The bad news is that more people than ever can do so. Competition levels are fierce as a result of all the new entrants. Because there are so many competitors and products, particularly in digital markets, there is a lot of noise that companies must cut through to be financially successful. All this competition translates into more price discounting, which creates lower margins and lower overall inflation. While the cost of creating and distributing these digital products can potentially enable high gross margins if barriers to entry can be created, below the “gross margin line,” huge amounts can be spent on sales and marketing to break though the noise. In short, getting into business with a product is easier than it has ever been, but getting discovered is harder.

- “There is [often] a generous free level, which means the only friction entailed in giving the product a try — or in accepting an invitation — is said sign-up.”

Software as a service (SaaS) is not just a new way to deliver services. It also a way to market software. By using the freemium model Thompson is talking about customers typically get some level of functionality for free and are charged a fee for more other services that are typically more advanced. Freemium is used in both consumer and business-to-business settings. Freemium is sometimes also called a land and expand business model. This term captures the idea that the free offer is used to “land” the customer which creates what is known as a sales lead. Why is the cost of sale so much lower? Most importantly the cost of educating the potential customer about the benefits of the product go way down once they have used the product in the free setting. The paid salesperson who patiently explains the services has been replaced by self-education. John Vrionis describes the less costly and more effective freemium sales process: ‘Evangelizing a new religion is very hard work, and more importantly it is expensive. But that’s essentially what selling proprietary software is like. Conversely, selling bibles to a group of believers is a lot easier. Sales people engage an account when they know that the prospect is well down the path of adoption and belief.” In some settings the salesperson can be eliminated completely as the customer sells themselves with self-service capabilities of the company web site. Venture capitalist Tom Tunguz writes about whey the freemium business model works so well:

“At its core, freemium is a novel marketing tactic that entices new users and ultimately potential customers to try a product and educate themselves about its benefits on their own. By shifting the education workload from a sales team to the customer, the cost of sales can decrease dramatically… freemium startups leverage usage data to improve their product. The large amount of users using the product enables A/B testing with statistical significance, a non-trivial strategic advantage. Marketing teams can sift through the data to understand market segmentation and funnel efficiency, and product management can parse the data to improve the on-boarding experience. Third, freemium startups gather information about their customer base to prioritize their sales efforts. When customers sign up or download a free product, freemium companies should gather data about the user to understand who they are and analyze the usage patterns of these users. With enough user data, it’s possible to predict with great accuracy which users will become large accounts.

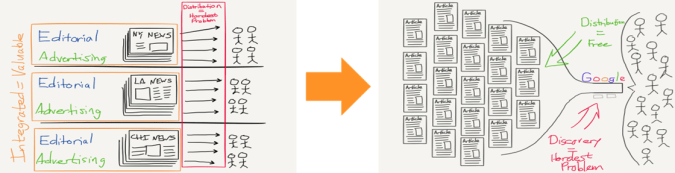

- “The Internet has made distribution (of digital goods) free, neutralizing the advantage that pre-Internet distributors leveraged.” “The end of gatekeepers is inevitable. We can regret the change or relish it, but we cannot halt it.” “In a world where the default news source is the Facebook News Feed, the New York Times is breaking out of the inevitable modularization and commodification entailed in supplying the “news” to the feed. That, in turn, requires building a direct relationship with customers: they are the ones in charge, not the gatekeepers of old — even they must now go direct.”

The cost of distributing the service to customers approaches zero since the customer pays for their own bandwidth and the devices needed to consume the service. For example, once upon a time the printing presses and physical distribution systems created barriers to entry in the newspaper business. This illustration by Thomson makes the point clearly

Once the need for that disappeared, the business model for journalism needed a re-boot. Business are still struggling to discover that new model. Fortunately, people like Thompson and companies like The New York Times are finding success with a subscription model.

The implications of this shift are huge and not just financial in nature. There are no longer huge newspapers in every city and nationally that are able to shape public opinion in the same way but rather hundreds of thousands of potential new sources occupying every available niche. This has atomized not just the journalism industry but society itself. Hundreds of thousands of journalism “flowers” have bloomed, and some of which are poisonous. As much as someone might like to go back to the old system of a few newspapers and televisions new programs guiding public opinion toward the political center by deciding what is “fit to print,” it is not possible to do so. The world has changed and we need to find a way to make this new frictionless creation reality functional.

Thompson himself is an example of how publishers can flourish financially in a business niche rather than trying to appeal to the mass market. In the advertising-supported business model era the products sought breadth of distribution to get millions of readers and therefore tended to write shallow but broad content to appeal to as many people as possible. In a world where paid subscription-based business models work best, greater depth in written material about a topic is now a feature rather than a bug. For example, Bill Bishop has created an email newsletter called Sinocism about current affairs in China. Bishop has attracted an audience of more than 30,000 readers who pay $11 a month or $118 a year for a membership. Other writers are seeing what Thompson, Bishop and and others are doing to support their work financially and are creating deep dive subscription newsletters covering topics like the NBA.

11. “Breaking up a formerly integrated system — commoditizing and modularizing it — destroys incumbent value while simultaneously allowing a new entrant to integrate a different part of the value chain and thus capture new value.”

The desire of a business founder to “integrate a different part of the value chain” has produced some of the most spectacular financial returns in the venture capital industry. This has been true since the creation of eShop which was a precursor to eBay. I love this story from a Patrick O’Shaughnessy podcast (as transcribed by Zach Ullman) since it is told by one of my favorite venture capitalists about his friend and mine Bruce Dunlevie:

Andy Rachleff: “One of our first very successful companies was eBay. Now this is a classic venture capital story, and it incorporates why Bruce Dunlevie is so great. The founder of eBay Pierre Omidyar actually started the company as a hobby. He had never intended for it to be a business. Previously, he was the number four…he was the fourth engineer hired into one of the first pen based computing software companies, a company called Ink. Back in Merrill, Pickard days, Bruce made an investment in Ink so we could have a play in pen based computing. He didn’t go on the board but he made an investment. Bruce was such a great advisor that even though he wasn’t on the board, anyone in the company who had a serious strategic question would come to Bruce rather than one of the board members and Omidyar was no exception. Well Ink pivoted into ecommerce. It was the first ecommerce company and changed its name to eShop. It was ultimately acquired by Microsoft. But eShop was the first company doing ecommerce on top of the CompuServe platform, so before the internet. After he left eShop, I think he joined a company called General Magic and he ran this electronic community of his apartment and he called it eBay for ‘electronic bay area.’ Bruce said: ‘you know Pierre I think you’re onto something here.’ We met the company and it struck us all that this platform that was being applied to collectibles and when people wanted to insult us ‘Beanie Babies, really? That’s what this thing is for?’ We saw it as an opportunity to sell many other things besides Beanie Babies or Pez dispensers. That was the leap of faith. That was the non-consensus idea. It wasn’t until the company went public that people stopped making fun of us.”

If there is something innovative that exists in the venture capital business today, Rachleff and Dunlevie are inevitably involved in it somehow.

- “The internet enables niche in a massively powerful way. “And because you’re not constrained to a geographic area, you can reach the entire world. “If you can get a niche and own it, you can do something valuable there. And the key thing is, the business models come with it. It had to be subscription. To do an ad-based sort of business, you’re just getting backed up behind Facebook and the New York Times like everyone else, and there’s no way to break through.” “I can publish what I need without needing to pay a newspaper or a printing press or any of that stuff. So from that perspective, the opportunity for a writer to go at it alone has never really existed previously.”

With his Stratechery newsletter and its paywall-based subscription business model, Thompson is pioneering a new way to make a living in an Internet age. He has been able to tap into a large community of people distributed globally who value his work. This approach enables Thompson to live where he wants to live (Taiwan) on his own terms. A venture capitalist said to me last week that he thought Thompson’s work was better because he works in a different time zone than most of the people and businesses he writes about. We agreed that this phenomenon is similar to how Warren Buffett benefits from working in Omaha. Thompson has no boss or employees. He is interrupted less often and he is less likely to get caught up in mindless imitation. His business is scaling very well and he is making a positive difference in the world as a teacher.

Notes:

My blog post on multi-sided markets: https://25iq.com/2016/10/22/a-dozen-things-ive-learned-about-multi-sided-markets-platforms/

My blog post on scalability: https://25iq.com/2017/08/25/a-dozen-attributes-of-a-scalable-business/

Some Posts from Thompson (but read the entire newsletter start to finish):

https://stratechery.com/2017/goodbye-gatekeepers/

https://stratechery.com/2015/aggregation-theory/

https://stratechery.com/2017/defining-aggregators/

https://stratechery.com/2015/netflix-and-the-conservation-of-attractive-profits/

https://stratechery.com/2016/chat-and-the-consumerization-of-it/

Related posts:

https://www.recode.net/2017/2/14/14612178/ben-thompson-stratechery-publishing-news

https://www.techinasia.com/stratechery-solo-ben-thompson-asia-apple-shifting-tides-online-media

https://medium.com/@swyx/ben-thompson-on-ben-thompson-aed48fbcbe82

http://avc.com/2009/04/the-venture-capital-math-problem/

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a3b0/30ec6a61a7042029abfabef85d5d2f68154a.pdf

Categories: Uncategorized