Every business owner has customer acquisition cost (CAC). And a belly button. If that business owner does not know their CAC they are essentially the equivalent of a blindfolded poker player. Every shareholder is a partial owner of the business in which they own shares. If they want to make intelligent decisions about the value of that partial ownership interest in the business, they must understand CAC.

CAC is a key element in the unit economics of a business, which can tell the owner whether the business is healthy. Unit economics are determined by understanding the direct revenues and costs associated with a business model expressed on a per unit basis.

Looking at a few CAC examples is helpful in understanding the concept. As an aside, in a subscription business CAC is often called SAC (subscriber acquisition cost), but the terms are essentially interchangeable. Another term you may see is CPGA (cost per gross addition). None of these terms is defined under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)and definitions may vary from company to company and over time. That GAAP is way behind the times on issues like defining CAC and customer churn is an understatement.

Satellite TV is a good example of a business that has high CAC. Here are some numbers for DISH:

The high CAC of DISH is only financially supportable with a multi-year contract since the potential for losing customers (churn) before that CAC is recovered exists. CAC and churn are reflexive. For example, if you require a a customer to sign a contract for months or years, CAC rises since customers must forgo opportunity to cancel if circumstances change (long term contracts requires customers to incur opportunity cost). If you do not require customers to sign and contract and they can cancel at any time CAC is lower but you risk not recovering CAC due to churn.

There are many other examples of real world CAC. For example, magazines, restaurants, credit cards, health clubs all have well-known CAC. People have created many entire new products to deal with the impact of CAC and churn over the years. As another example, prepaid cellular was created to lower CAC and to deal with the fact that many people can’t pass a credit check.

Buying keywords is another way to incur CAC. A sample calculation is:

“Assume a cost “per click of 50 cents, and the resulting website visitors converting to a trial at the rate of 5%. Those trials are then shown converting to paid customers at the rate of 10%. What the sheet shows is that each customer is costing you $100 in just lead generation expense. For many consumer facing web sites, it can be hard to get the consumer to pay more than $100 for the service. And this cost does not factor in the marketing staff, web site costs, etc.”

If 10% of leads turn into a sale, CAC is at least $1,000 since there will be other expenses.

Someone may say about the concepts discussed in this post: “This is too complex. I don’t like math.” If that is the case, it is wise to buy a diversified portfolio of low cost index funds. Investing requires some math. The good news is that it is not complex math. Operating a business also requires math, but in both cases no more than high school algebra is required.

Is there any way to reduce CAC? Yes. Some people spend their entire working lives trying to make this happen. One way to lower CAC is to have people spread the word via viral invitations sent by existing customers. This can happen, but it takes an existing customers to get a new customer by word of mouth. Something must kick start the process. The other way to reduce CAC is via cross selling or selling new services or products to existing customers. It is easier and less expensive to sell to customers who are already using your products than to sell something to a completely new customer. Wells Fargo recently took this approach cross selling way too far and created some serious problems as a result. Another way to reduce CAC is to use the “freemium” business model, which is about getting people to use products or services and then trying to create a upsell opportunity.

Companies do not generally like reporting CAC or SAC for reasons that will be explained below. As an example, Netflix no longer reports SAC, but when it did:

Another example of SAC is the mobile phone business. The pink line shows the SAC for a mobile business expressed in Euros in this case (contract not prepaidcustomer):

Bill Gurley has an excellent explanation of how CAC can be used in a lifetime value model, with emphasis on how it can be misused. When looking at LTV is is wise to remember that all models are wrong, but some models are useful. The LTV model must be used carefully and is only as good as the assumptions in the model. Gutley writes:

“Lifetime value is the net present value of the profit stream of a customer. This concept, which appears on the surface to be quite benign, is typically used to compare the costs of acquiring a customer (often referred to as SAC, which stands for Subscriber Acquisition Costs) with the discounted positive cash flows that will come from that customer over time. As long as the sum of the discounted future cash flows are significantly higher than the SAC, then people will argue it is warranted to “push the accelerator,” which typically means burning capital by aggressively spending on marketing.

This is a simplified version of the formula:

The key statistics are as follows:

- ARPU (average revenue per user)

- Avg. Cust. Lifetime, n (This is the inverse of the churn, n=1/[annual churn])

- WACC (weighted average cost of capital)

- Costs (annual costs to support the user in a given period)

- SAC (subscriber acquisition costs, sometimes referred to as CAC)

The LTV formula, when used correctly, can be a good tactical tool for monitoring and comparing like-minded variable market programs, especially across channels. But like any model, its proper use is entirely dependent on the assumptions used in that model.

Something unprecedented is impacting all business models right now and it is causing people a great deal of confusion and angst. Central bank policies have taken the cost of capital (WACC) down to levels we have never seen before at a time that is technologically unlike any we have ever seen before. When WACC falls precipitously and platform businesses see the opportunity to generate network effects and critical mass they can get very aggressive on customer acquisition spending since the tape measure grand slam home run potential of doing so has never been higher. Bill Gurley noted this past week that this phenomenon has resulted in: “a massive increase in speculative behavior. If you can make low prob/high outcome bets with OPP [other people’s property], why not?” Understanding why this is happening is made clearer when you consider Warren Buffett’s suggested formula: “Take the probability of loss times the amount of possible loss from the probability of gain times the amount of possible gain.” Wagers in platform businesses are being made at a time when outcomes are highly convex (massive upside potential and limited downside potential). Magnitude not frequency of success matters. Some people are swinging for the fences right now given the low cost of capital and the magnitude of a potential win. If your competitor does this you need to decide whether you play the game that is on the field. Or not.

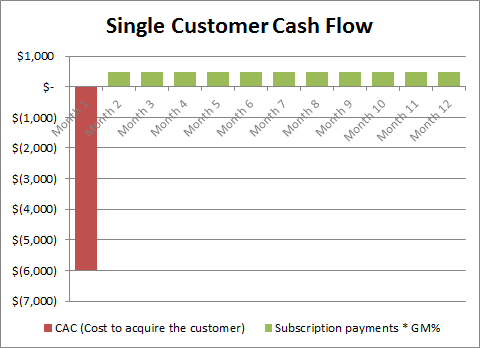

CAC is a particularly important part of a lifetime value computation for a business since it is paid up front and that means cash going out the door in month one of the customer relationship. David Skok explains the cash flow issue here:

“To illustrate the problem, we built a simple Excel model which can be found here. In that model, we are spending $6,000 to acquire the customer, and billing them at the rate of $500 per month. Take a look at these two graphs from that model:

To compute its CAC a business takes its entire cost of sales and marketing over a given period, including salaries and other headcount related expenses and divides it by the number of customers acquired during that period. If a business spent a total of $1,000 on sales and marketing in a month and acquired 100 customers in the same month CAC is $10.00. This calculation of CAC is done on a “gross” customer acquisition basis since customers lost during the period (churn) is considered separately in the LTV formula.

In calculating CAC, everything that is a cost of customer acquisition must be considered or CAC is not fully loaded. Some costs that go into CAC are more obvious like any wages and commissions paid related to marketing and sales, the cost of all marketing and sales software and additional related professional services. Other elements in CAC are more subtle and sometimes hidden.

“The following list includes time and/or other items that you may be ignoring as part of your acquisition costs:

- The time you spend on getting people onto your sales pipeline – typically may become the job of a sales person down the road

- The time you spend on Social Media outreach

- The time you spend Networking at Events

- The time you spend converting a customer from warm to paying – typically may become the job of a sales person down the road

- The time you spend on support or install calls to help a customer roll out the product within their network – might become the job of a sales engineer down the road

- Integration work to include your product into their system or data flow – might become the job of a consultant, or sales engineer down the road

- Supplier calls or deals (with minimums to help provide you with the necessary inventory to sell onto your new customers.

- Sales Channel calls or deals – do you need to spend time setting these up or actually even splitting revenues? “

Other additions to CAC may look like cost of goods sold or COGS but are actually a part of CAC. The amount a company pays for a retail store lease near a popular street location is in part CAC. The cost of “loss leader” goods and services offered to potential and actual customers is also part of CAC. “Free” X for customers as a loss leader may look like COGS but it is CAC. In some situations the loss leader business model is called freemium. Sometimes the product or service is actually free and sometimes it is offered at a subsidized price. In other words, sometimes COGS is disguised CAC.

This analysis of Amazon Prime by Cowen is a good example of an all in LTV calculation that includes SAC of $312 and a lifetime value of $2,960:

Sometimes you will hear someone say: “I don’t spend anything on marketing. It’s all word of mouth.” The reality is that word of mouth does not happen by accident and inevitably a lot of time and energy was expended to create viral customer acquisition. Creating product virality requires work and most always some money.

Sometimes you will also hear people talk about what Sam Altman talks about below:

“There are now more businesses than I ever remember before that struggle to explain how their unit economics are ever going to make sense. It usually requires an explanation on the order of infinite retention (“yes, our sales and marketing costs are really high and our annual profit margins per user are thin, but we’re going to keep the customer forever”), a massive reduction in costs (“we’re going to replace all our human labor with robots”), a claim that eventually the company can stop buying users (“we acquire users for more than they’re worth for now just to get the flywheel spinning”), or something even less plausible. Most great companies historically have had good unit economics soon after they began monetizing, even if the company as a whole lost money for a long period of time. Silicon Valley has always been willing to invest in money-losing companies that may eventually make lots of money. That’s great. I have never seen Silicon Valley so willing to invest in companies that have well-understood financials showing they will probably always lose money. Low-margin businesses have never been more fashionable here than they are right now. Burn rates by themselves are not scary. Burn rates are scary when you scale the business up and the model doesn’t look any better. Burn rates are also scary when runway is short (i.e., burning $2M a month with $100M in the bank is fine; burning $1M a month with $3M in the bank is really bad) even if the unit economics look great.”

Recently we have seen a number of writers talk about businesses “losing money” based on information that sources have given them from an income statement. This is not surprising since many growing business may be incurring a loss on their income statement because CAC happens in month one. That loss may be acceptable if the acquisition of the revenue from the customer creates value. Or not. Without more data than just the income statement you just don’t know.Would you accept a $40 cash outflow in month one if a credit worthy customer agreed to pay you $10 a month for a year? If you had enough cash that return is attractive over the long term.

One key to wise growth is making sure what Warren Buffett wrote in his 1992 letter is true:

“Growth is always a component in the calculation of value, constituting a variable whose importance can range from negligible to enormous… Growth benefits investors only when the business in point can invest at incremental returns that are enticing – in other words, only when each dollar used to finance the growth creates over a dollar of long-term market value. In the case of a low-return business requiring incremental funds, growth hurts the investor. In The Theory of Investment Value, written over 50 years ago, John Burr Williams set forth the equation for value, which we condense here: The value of any stock, bond or business today is determined by the cash inflows and outflows – discounted at an appropriate interest rate – that can be expected to occur during the remaining life of the asset. Note that the formula is the same for stocks as for bonds. Even so, there is an important, and difficult to deal with, difference between the two: A bond has a coupon and maturity date that define future cash flows; but in the case of equities, the investment analyst must himself estimate the future “coupons.” Furthermore, the quality of management affects the bond coupon only rarely – chiefly when management is so inept or dishonest that payment of interest is suspended. In contrast, the ability of management can dramatically affect the equity “coupons.”

Rules of thumb have emerged regarding the “right” level of CAC in relation to LTV. David Skok lays out the current conventional wisdom:

“Over the last two years, I have had the chance to validate these guidelines with many SaaS businesses, and it turns out that these early guesses have held up well. The best SaaS businesses have a LTV to CAC ratio that is higher than 3, sometimes as high as 7 or 8. And many of the best SaaS businesses are able to recover their CAC in 5-7 months. However many healthy SaaS businesses don’t meet the guidelines in the early days, but can see how they can improve the business over time to get there. The second guideline (Months to Recover CAC) is all about time to profitability and cash flow. Larger businesses, such as wireless carriers and credit card companies, can afford to have a longer time to recover CAC, as they have access to tons of cheap capital. Startups, on the other hand, typically find that capital is expensive in the early days. However even if capital is cheap, it turns out that Months to recover CAC is a very good predictor of how well a SaaS business will perform. Take a look at the graph below, which comes from the same model used earlier. It shows how the profitability is anemic if the time to recover CAC extends beyond 12 months. I should stress that these are only guidelines, there are always situations where it makes sense to break them.”

People often under-rate the importance of great distribution and specifically organic customer acquisition. It is often the case that CAC early in the life of a business is very high and that it can trend down over time if the right approaches are taken. Sirius Satellite radio is an example of a business that has seen its CAC drop significantly over time from very painful levels. Founders of startups often make wild claims about their ability to reduce CAC. Marc Andreessen said once: “Many entrepreneurs who build great products simply don’t have a good distribution strategy. Even worse is when they insist that they don’t need one, or call no distribution strategy a ‘viral marketing strategy’ … a16z is a sucker for people who have sales and marketing figured out.” Just hoping that an offering will go viral is not going to lead a company to success since something going viral is rarely an accident. Acquiring customers cost effectively is the essence of business. Almost always the best way to acquire customers cost effectively is with an organic customer acquisition strategy. In contrast, formulating a strategy based on buying advertising is unlikely to be successful.

The final point related to the inherently connected nature of CAC. Bill Gurley helped me improve my metaphor when he wrote this:

“Tren Griffin, a close friend that has worked for both Craig McCaw and Bill Gates refers to the five variables of the LTV formula as the five horsemen. What he envisions is that a rope connects them all, and they are all facing different directions. When one horse pulls one way, it makes it more difficult for the other horse to go his direction. Tren’s view is that the variables of the LTV formula are interdependent not independent, and are an overly simplified abstraction of reality. If you try to raise ARPU (price) you will naturally increase churn. If you try to grow faster by spending more on marketing, your SAC will rise (assuming a finite amount of opportunities to buy customers, which is true). Churn may rise also, as a more aggressive program will likely capture customers of a lower quality. As another example, if you beef up customer service to improve churn, you directly impact future costs, and therefore deteriorate the potential cash flow contribution. Ironically, many company presentations show all metrics improving as you head into the future. This is unlikely to play out in reality.”

It is always wise to be be careful out there in running or owning a stake in a business since CAC can be a stone cold killer.

Notes:

Bill Gurley on LTV: http://abovethecrowd.com/2012/09/04/the-dangerous-seduction-of-the-lifetime-value-ltv-formula/

David Skok: http://www.forentrepreneurs.com/saas-metrics-2/

Sam Altman on Unit Economics: http://blog.samaltman.com/unit-economics

Buffett 1992 letter: http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1992.html

Recode quoting Cowen on Amazon Prime: http://www.recode.net/2016/10/5/13175272/amazon-prime-valuation-worth-143-billion-cowen-report

Seed Camp: http://seedcamp.com/resources/whats-your-real-customer-acquisition-cost/

Categories: Uncategorized