5. “We’re competing with sleep, on the margin. It’s a very large pool of time.” “We are growing a whole industry. So [Netflix faces] a mix of competition that hurts, but on the other hand that competition is making internet viewing more popular with everyone.” “Every incremental 10 million is a little harder than the last 10 million, but our content keeps getting better, so those forces offset each other. When you look at the last five years, everyone was worried every quarter about saturation in the U.S., and we’ve just continued to grow. But it doesn’t mean it’s going to be inherently forever. But we certainly feel good about the near-term as we’re expanding and just getting bigger content budget, more shows, more marketing and so all of that feels very good. I don’t see anything that’s going to stop Netflix from getting to most people in the United States and then eventually hopefully most people around the world. But we’re just going to focus on the everyday of making the services better and better.” “Amazon is an amazing company and doing so many different things, it’s really incredible. But I’m not sure if it will really affect us very much, because the market is just so vast.”

Netflix has nearly 118 million streaming subscribers on a global basis, adding 8.3 million subscribers last quarter alone. 3.4 million Netflix customers still get DVDs by mail.

How much Netflix will grow its customer base in the future is not predictable with certainty, but that does not mean people are not willing to guess. For example, BTIG analyst Richard Greenfield believes Netflix will exceed 200 million global streaming subscribers by 2020. Hastings himself said on January 18, 2018 that “it was five years ago when we said we thought the market in the U.S. would be somewhere between 60 million and 90 million. We’re still only at 55. So we got a ways to go just to cross into the bottom of our expectation range.” International growth is important for Netflix. The web site Market Realist has complied this chart of international growth for Netflix;

In terms of growth in general, Hastings makes a point that I saw myself in the early days of mobile phone service in the last 1980s. In those days there was an A and a B side mobile service provider. This meant that in any given city there was only a maximum of two competitors. But sometimes only the A or B side operated in a city for a while. What we experienced then was that sales were significantly higher in cities where there was competition from both A and B. As Hasting notes above, sometimes the presence of a competitor or competitors like Hulu, Disney or HBO can help grow a market. The market for software as a service (SaaS) seems to be similar in that intense competition among providers is growing the market for everyone.

6. “Prices are relative to value. We’re continuing to increase the content offering and we’re seeing that reflected in viewing around the world. So we try to maintain that feeling that consumers have that were a great value in terms of the amount of the content we have relative to the prices. If you look at the long-term trend in our business, we’ve grown the content budget, we’ve grown the content library, but revenues have come faster, which is what’s driven the profit improvement and the margin improvement over the years.”

One of the most important questions in assessing the value of a business like Netflix is the extent to which it has pricing power. Warren Buffett believes: “The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you must have a prayer session before raising the price by 10 percent, then you’ve got a terrible business.” Can Netflix increase prices and not see a big increase in churn that offsets the benefits of that price rise for the company? That’s the sort of question that is always relative. How much pricing power does Netflix have? The best test of that is what actually happened when Netflix raised prices last year. Hasting said this in an earnings call on January 22, 2018: “We moved from roughly €10 to €11 in Europe or $10 to $11 in the U.S., so about a 10% increase. And we saw very little effect on sign ups and growth and thus as you said the really strong results.” That’ a good sign.

I have written on pricing power before in my post on how See’s Candies changed how Buffett thinks about a business. Munger puts it this way in the case of Disney: “There are actually businesses, that you will find a few times in a lifetime, where any manager could raise the return enormously just by raising prices—and yet they haven’t done it. So they have huge untapped pricing power that they’re not using. That is the ultimate no-brainer. Disney found that it could raise those prices a lot and the attendance stayed right up. So a lot of the great record of Eisner and Wells came from just raising prices at Disneyland and Disneyworld…”

7. “We intentionally called the company Netflix and not DVD by mail.” “When I was a computer science student, I took the classic course everyone takes on networking technology. And one of the things that is mentioned in that is this example of, what is the speed of the transfer of bits in a station wagon that is filled with backup tapes and driving across the U.S. When I heard about the DVD, I realized, that’s a digital distribution network. We knew that over time, the Internet would overtake the postal service. It didn’t happen till ten years later. In 2007 was the very first streaming.” “It’s a race, but there are going to be many winners.” “If you can build an iPhone app, you can start a TV channel. We are going to have to see how that plays out.” “Now, what we’ve done is invest in codecs so that at half a megabit [per second], you get incredible picture quality.” “We’re now at about 300 kilobits per second, and we’re hoping someday to get down to 200 kilobits. So we’re being more and more efficient with operators networks.” “We want to make buffering a historic relic like where your kids say to you, ‘what’s buffer?’”

Marc Randolph was the other a Netflix co-founder, but left the company in 2002. CNBC describes his version of the Netflix origin story:

“[Randolph] and Hastings decided they wanted to create the Amazon.com of something. Randolph has also said that they “decided on shipping DVDs because customers were willing to buy them online and they were strong enough to mail. Since they couldn’t get a DVD — which was new technology at the time — they mailed a CD a few blocks to see how it would hold up. When it arrived in one piece, they decided to start Netflix.”

The trade-offs that the Netflix co-founders were dealing with are issues that I have been dealing with for most of my career. These trade-offs are particularly important to get right in an era where cloud computing is so important.

It was my great fortune in life to be able to work with Jim Gray, who wrote one of the best papers ever written on what he called “distributed competing economics.” Gray dealt often with huge quantities of astronomy data. Due to cost and time issues. scientists often sent each other hard drives via UPS or Federal Express rather than use communications networks for transmittal of that data. Jim understood well the challenges of being a network services provider since he was a customer. In his wonderful paper that I mentioned Jim wrote about the key trade offs:

“What are the economic issues of moving a task from one computer to another or from one place to another? A task has four characteristic demands:

- Networking – delivering questions and answers,

- Computation – transforming information to produce new information,

- Database Access – access to reference information needed by the computation,

- Database Storage – long term storage of information (needed for later access).

The ratios among these quantities and their relative costs are pivotal. It is fine to send a GB over the network if it saves years of computation – but it is not economic to send a kilobyte question if the answer could be computed locally in a second.”

Making the right trade offs is at the heart of cloud computing unit economics. What should be done at the core of the network and what should be done at the edge of the network? When should a communications network be used to move large amounts of data and when should something be delivered in a hard drive? What sort of latency penalty (lag or delay) is acceptable with a service? Eventually because of changes in distributed competing economics it became cheap enough for Netflix to make the transition to streaming. Hasting has said that he knew that it was finally possible to stream commercial video when he saw the success of YouTube. It is refreshing to hear someone say so openly that he gives credit to another company for being first. YouTube, Netflix and Amazon are competitors but also arguably each found unique product/market fit.

As an aside, this account in The New York Times misses by a mile how much innovation took place at Xerox PARC, but it does describe a business that was first to market, but not first to product/market fit:

The technologists at the lab, the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, did not invent the computer mouse and graphical-user interface. But they refined them and built a usable prototype personal computer, the Alto. More than 1,000 Altos were made and put to work, including a few in Jimmy Carter’s White House. At Xerox, when the corporate managers took over its personal computer project and tried to commercialize the Alto, named the Xerox Star, they priced it at more than $16,000. It flopped. The Xerox Star was priced more like a copier, an expensive office machine, rather than a personal computer. In 1981, the same year the Star came to market, IBM introduced its PC for business, pricing it at less than $1,600. Three years later, the Apple Macintosh sold for about $2,500.

The price of the Xerox Star was equivalent to $44,415 in 2017 so it really wasn’t priced like a personal computer. As an aside, in 1980 I was using a Wang Word processor at work. That was the year Bill Gates Sr. first told me about Microsoft. He said: “People are saying this company will be important someday.” I saw my first IBM PC in 1982. In 1983 I bought an Apple II clone for a few hundred dollars in Seoul Korea for use at home. I used it to play games and as a word processor. I wrote my first book on that machine. The Wang world processor disappeared from offices in the mid-1980s replaced by desktop machines.

8. “We’re fundamentally in the membership happiness business, as opposed to in the TV show business. Once you subscribe, our interest is purely your happiness.” “If you didn’t own a cable networks you couldn’t break into the business. Which mean there was a significant constraint which gave then huge margins.”

In Robbie Baxter’s book The Membership Economy she writes: “‘membership’ is an attitude, whereas a ‘subscription’ is a financial arrangement.” She describes how the business environment is transitioning from providing “ownership to access, from anonymous transactions to known, formal relationships and from one-way messaging to two-way communications between the organization and its members, but also conversations among the members themselves, under the umbrella of the organization.” What enables the membership economy is the connected always on relationship that delivers telemetry data about customers plus machine learning. According to Baxter people who feel like “members” will ideally experience (1) success in finding happiness, which triggers daily habits; (2) trust in the service in terms of both happiness and things like privacy and security; and (3) an emotional connection with the service that creates a “sense of belonging.”

Amazon is a poster child for a membership strategy as is Netflix:

“More new paid members joined Prime in 2017 than any previous year—both worldwide and in the US” said the company in its latest earning release.

9. “We need more sophisticated metaphors than ‘only the paranoid survive.’ Paranoid people are delusional.”“We spend almost no time [at Netflix] thinking about competitors. We spend almost all our time thinking about customers.”

Hastings is taking issue with a famous Andy Grove idea above. Hastings believes focusing on competitors takes your eyes off the needs of the customer. A departing Google engineer created a stir recently making a similar point. CBNC describes this engineer’s remarks:

He criticized it for becoming “100% competitor-focused” and said the company “can no longer innovate.” Steve Yegge, who joined Google from Amazon in 2005, wrote a blog post about his decision t quite the company saying it has become too focused on competitors instead of customers. He said product launches such as its smart speaker, Home, its chat app Allo and its Android Instant Apps copy Amazon Echo, Facebook-owned WhatsApp and WeChat, respectively. “Google has become 100% competitor-focused rather than customer focused,” he wrote. “They’ve made a weak attempt to pivot from this, with their new internal slogan ‘Focus on the user and all else will follow.’ But unfortunately it’s just lip service.”

There is always a tension between people who are focused on making an existing business model perform and people who create a genuinely new business model. Some people are good at one thing and some are good at the other. Other people are good at both.It depends.

- “We had to lay off 1/3 of the company in 2001 [from 120 people to 80]. We eked our way into profitability and survived. After 2002, we realized we were going to survive and thought, it would be awful not to want to work here.”

The unfortunate experience Netflix had with layoffs in 2001 resulted in a rethinking of many aspects of the company’s culture and human resources systems. The outcome of this process was originally reflected in a famous 2009 Netflix “culture” slide deck. For example, one of the slides was:

Netflix would later reformat the points made in these slides into a narrative document that has been very influential. You can find a link to that document in the end notes.

- “The drive toward conformity as you grow as a company is very substantial” “You should have more things that don’t work out. You should get more aggressive.” “How did distribution innovate in the movie business in the last 30 years? Well, the popcorn tastes better, but that’s about it.” “Our hit ratio is way too high right now. So, we’ve canceled very few shows … I’m always pushing the content team: We have to take more risk; you have to try more crazy things. Because we should have a higher cancel rate overall.”

Hastings had experiences at his first company (Pure Software) that caused him to try to stop the creation of processes at Netflix that stifle innovation and creativity. Hastings views on the dangers of conformity remind me of the Jeff Bezos “Day One” concept. Bezos describes his objective in this way:

“I’ve been reminding people that it’s Day 1 for a couple of decades. I work in an Amazon building named Day 1, and when I moved buildings, I took the name with me. I spend time thinking about this topic. ‘Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1 [here at Amazon].”

- “As an entrepreneur you have to feel like you can jump out of an airplane because you’re confident that you’ll catch a bird flying by. It’s an act of stupidity, and most entrepreneurs go splat because the bird doesn’t come by, but a few times it does.” “I’m on the Facebook board now. Little did they know that I thought Facebook was really stupid when I first heard about it back in 2005.”

Hastings is making a statement that reflects the data on startups, most notably venture backed startups. The data makes clear that most startups will fail to achieve their goals. This is inevitable since no system can produce real world innovations without some failure. Really big ideas that are capable of generating venture capital style returns often seem like a bad idea at first as Facebook did not Hastings. Of course, some ideas that seem like a bad idea really are a bad idea (or are a good idea that is too early to capitalize on). One helpful technique for more accurately assessing what startup investments to make given uncertainty, risk and ignorance can be illustrated by looking at an example.

Assume there is a startup called Weed-2-Door that delivers weed right to its customer’s home in areas where cannabis is legal. Weed-2-Door, like other startups, faces many challenges. Four of these key challenges are:

- How big is the market?

- Can regulatory issues be overcome?

- Will the company have enough cash to get to cash flow positive?

- Can the right team be created to build the business?

What is the best way for an investor to evaluate whether Weed-2-Door will be a commercial success given these and other challenges?

Many experienced investors like Elon Musk are proponents of using decision tree analysis in a situation like this. As another example, Charlie Munger points out: “One of the advantages of a fellow like Buffett is that he automatically thinks in terms of decision trees and the elementary math of permutations and combinations.”

What are these decision trees that Charlie Munger is talking about? In short, they are a way of representing decisions using a tree-like structure. More technically:

Decision trees have their genesis in the pioneering work of von Neumann and Morgenstern. Decision trees graphically depict all possible scenarios. The decision tree representation allows computation of an optimal strategy by the backward recursion method of dynamic programming. Howard Raiffa called the dynamic programming method for solving decision trees “averaging out and folding back.” Influence diagram is another method for representing and solving decision problems.

Here is representation of a decision tree for a landlord who is choosing between leasing a property or using it as a base for their own business from a tutorial you can find in the end notes to this post.

Do you want to know the outcome of this analysis? Read the tutorial in the end notes below!

One of the reasons why decision trees are useful is the reality that anyone faces in making decisions that as based on future outcomes described by a bridge playing Harvard professor named Richard Zeckhauser. Munger has said: “The right way to think is the way [Harvard Professor Richard] Zeckhauser plays bridge. It’s just that simple.” It can be used in many situations. For example, Zeckhauser runs a quick decision tree in his head before deciding how much money to put in a parking meter in Harvard Square. “It sometimes annoys people but you get good at doing this.”

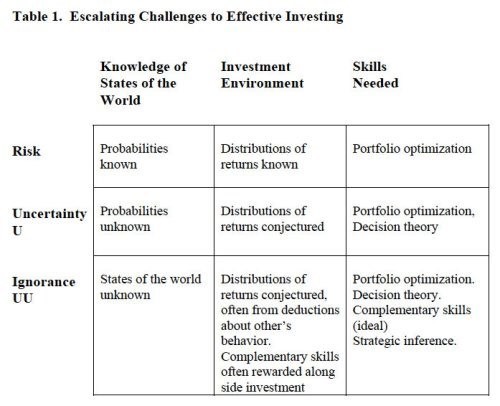

Key to all this is understanding the difference between risk, uncertainty and ignorance. Zeckhauser has written an insightful paper on this topic entitled “Investing in the Unknown and Unknowable” that I have linked to in the end notes. That paper has a chart which I refer to often. As you can see, Zeckhauser is saying that “decision theory” is an important approach in dealing with uncertainty and ignorance.

Zeckhauser writes with a colleague about trying to make predictions is a world where future states are not known and probability can’t be calculated,

“On the continuum that proceeds from risk to uncertainty, ignorance lies beyond both. Ignorance, we show below, is the starting point of a fertile, untapped area for decision research. Given that ignorance adds the additional complexity of unidentified outcomes, it encounters all the behavioral biases of uncertainty (some magnified), plus additional biases of its own. The rational decision paradigm employs the expected utility (EU) framework. That normative framework attaches a probability, often subjective, and a utility to each potential outcome. Finally, it prescribes that the decision maker assess the decision tree and choose the preferred branch. Alas, ignorance defeats the straightforward application of such methods: metaphorically, some branches of the tree remain shrouded in darkness. Compounding difficulties, the presence of ignorance often goes unrecognized: What is unseen is not considered.”

The best of the best investors understand how to assess probability and potential outcomes in a world that is mostly uncertain, often involves ignorance, and rarely is about risk as defined by Zeckhauser. Sometimes the best approach is to get in what Zeckhauser calls “the side car” of someone who you trust and who had the necessary complementary skills. Mark Cuban describes this “side car” approach to investing with an example: “If you say Jeff Bezos and Reed Hastings— those are my 2 biggest holdings. They’re just nonstop startups. They’re in a war. And you can see the market value accumulating to them because of that. They’re the world’s greatest startups with liquidity. If you look at them as just a public company where you want to see what the P/E ratio is and what the discounted cash value– you’re never going to get it, right? You’re never going to see it.” In deciding to be an investor in AMZN and NFLX Cuban is betting on Bezos and Hastings by getting in their “sidecar.”

End Notes:

Tutorial on decision trees: http://kwanghui.com/mecon/value/Segment%202_2.htm

Zeckhauser “Unknown and Unknowable” paper: https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/rzeckhau/InvestinginUnknownandUnknowable.pdf

Wall Street Analysts on NFLX: http://www.nasdaq.com/symbol/nflx/recommendations

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/31/business/dealbook/xerox-fujifilm.html

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=tCn4hdTI2jc

https://a16z.com/2017/02/25/reedhastings-netflix-entertainment-internet-streaming-content/

https://www.ceo.com/tag/reed-hasting-interview/

https://medium.com/cs183c-blitzscaling-class-collection/cs183c-session-16-reed-hastings-4e1058d2439f

http://educationnext.org/disrupting-the-education-monopoly-reed-hastings-interview/

http://mattturck.com/the-power-of-data-network-effects/

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.marketwatch.com/amp/story/guid/F54342E2-A397-11E7-9BA9-150476A55D7E

http://www.eugenewei.com/blog/2012/11/28/amazon-and-margins

https://www.recode.net/2018/1/22/16920150/netflix-q4-2017-earnings-subscribers

https://hbr.org/2014/01/how-netflix-reinvented-hr

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/05/23/netflix-ceo-reed-hastings-on-how-the-company-was-born.html

http://www.larryblakeley.com/Articles/computational_economics/jim_gray200303.pdf

https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/rzeckhau/InvestinginUnknownandUnknowable.pdf

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3aee/f75bebaf557e433c39bc7a206fa74b5c2e3e.pdf

https://www.intelligentinvestor.com.au/decision-trees-prevent-swaying

https://www.premierhealth.com/HealthNow/Linking-Brain-to-Computer–Science-or-Science-Fiction-/

“The Art and Science of Negotiation” (1982)

“Negotiation Analysis: The Science and Art of Collaborative Decision Making” (2002), co-authored with John Richardson and David Metcalfe.

http://web.stanford.edu/class/cee115/wiki/uploads/Main/Schedule/OverviewDA.pdf

https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/rzeckhau/Ignorance%20-%20Literary%20Light.pdf

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/pdf/10.1287/ited.2.3.64

https://hbr.org/2015/05/from-economic-man-to-behavioral-economics

https://www.safalniveshak.com/latticework-of-mental-models-permutation-and-combination/

https://medium.com/metamorphic-ventures/babe-ruth-power-laws-and-what-it-all-means-778dc1e788d2

https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/rzeckhau/Ignorance%20-%20Literary%20Light.pdf

Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/mar/15/netflix-ted-sarandos-house-of-cards

Categories: Uncategorized